Introduction

The United Kingdom’s economy is in very bad condition and has been for some time now. Britain’s economy is marked by low growth, rising debt, low productivity, prolonged high inflation and a lack of investment. The British government is burdened by debt and has its hands tied by rising interest rates and huge deficits, meanwhile British citizens are overtaxed and underpaid. Britons have to contend with exorbitant taxes, record high inflation and rising interest rates and the British government is bereft of ideas and solutions.

The depth of the UK’s economic problems is truly staggering, so much so that it is hard to put into words. Britain’s problems in housing, investment, debt, tax and in other areas have gradually built up over the years and go back a long way. As such, Britain’s economic problems aren’t necessarily easy to pinpoint: they span several decades, numerous governments, both of the main political parties and various prime ministers. All of this has caused significant problems in other areas too, the collateral effects of the struggling British economy has led to problems in healthcare, education, law enforcement, infrastructure and elsewhere. Ultimately, the UK has lots of problems and few solutions, and simply borrowing and spending its way out of these problems is no longer feasible. One does not wish to be a purveyor of negativity but baring a miracle I do not see how the British economy can be saved.

Background

The 2008 global economic crisis smashed the engine of Britain’s economic growth and, truthfully speaking, the country has not recovered since. Britain’s response to the crisis led to massive bailouts of the banks; this resulted in increased borrowing from the government and rising deficits. Since then, the UK has fallen into a prolonged period of low growth and the 2010s has become known as ‘the lost decade’. Since the 2008 crisis, the debt-to-GDP ratio of the country has grown and grown with GDP per capita having risen only slightly and debt increasing year-on-year. Simply put, Brexit has not gone according to plan with both exports and investment having both declined since leaving the European Union. Like many countries, the UK fell into recession during the COVID-19 lockdowns as health considerations took precedence over everything else, however the post-COVID boom was short lived because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. 45 chaotic days with Liz Truss as the prime minister sent the markets into a tailspin as the pound dropped to a record low against the dollar ($1.033) and the Bank of England had to parachute in with an emergency £65 billion rescue package to prevent the crisis from escalating.

The aftermath of the 2008 crisis saw the UK run unprecedented deficits as the national debt grew and grew. In response to this, the Conservative government embarked on a period of austerity, drastically cutting spending in an attempt to reduce the debt and restore confidence to the markets. The response to the 2008 global economic crisis ushered in a period of low interest rates and cheap credit. This led to increased borrowing (by households and the government), a booming bond market and large asset bubbles forming. This is okay when interest rates are low but now that rates have increased this borrowing and speculation is causing problems throughout the economy: for Downing Street, for industry, for the public sector and for British households. The good times of cheap credit are over, Britain’s luck has run out and its debts need to be paid back. The problem now is that the government can no longer kick the proverbial can down the road, these problems need to be addressed, and fast.

Low growth

Britain is a low-growth economy, we are in an extended period marked by very low growth, as in growth under 1% and there is no escaping that fact. It has been like this since the start of 2022 (see graph below) so we have had just under two years with growth below 1%. At the moment, we are seeing no growth at all and these figures are a clear sign of a struggling economy, this is steadily reducing the country’s living standards by forcing its citizens to pay higher taxes for poorer public services.

The GDP of the UK has hardly grown at all since 2019 and in those four years we have witnessed nothing but economic stagnation.1 The country’s low-growth rate is partly the result of a lack of investment and low productivity, two points I will come onto shortly.

What this all adds up to is a lower quality of living for Britons across the country, low growth in the economy means little real income gains for British workers, decreasing savings, more borrowing and higher debt, as well as increased housing, energy and food costs. At the bottom of the social and economic pyramid it equates to increasing poverty and destitution.2

While growth has stagnated, Britain’s population continues to grow exponentially, mainly due to rising immigration, and this means fewer goods and services for everyone. The combination of a growing population along with a stagnating economy has lead to a reduced standard of living for Britons.

Inflation and cost of living crisis

Britain’s cost of living crisis is the worst in half a century. It can be attributed to many things but rising inflation and high interest rates are the primary culprits.

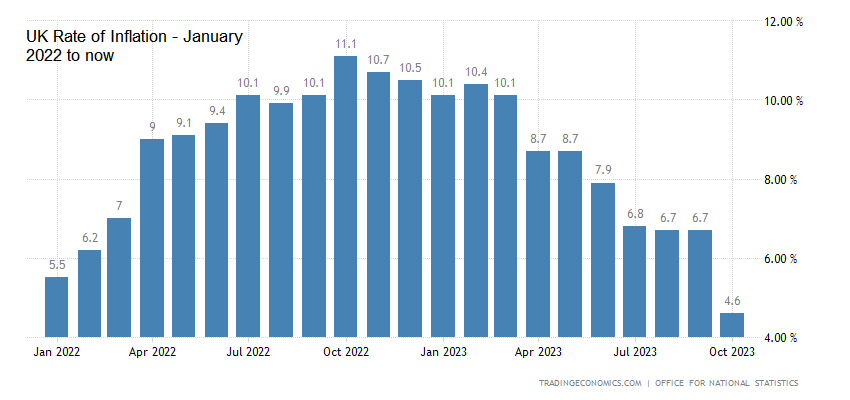

Inflation has come down recently to around 4.6% but for the majority of 2022 and 2023 the UK had been battling serious inflation which was actually in the double digits between August 2022 and March 2023. However, food inflation has soared by 13.2% in the last 3 months and the CPI (consumer price index) is still high.3 The annual increase in food inflation is a staggering 14.8%. To battle inflation, the Bank of England has had to raise interest rates and this has hurt consumers who compensate by spending less which means less money in the economy. Although decreasing, the current rate of inflation is still well above the Bank of England’s recommended rate of 2% and it will persist with high interest rates until inflation comes down to the 2% level. The war between Russia and Ukraine has led to rising food and energy costs but the truth is the UK had a cost of living crisis before the conflict started.

The interest the government pays on the national debt has reached a 20-year high as the rate on 30-year bonds reaches 5.05%. With interest rates high, London can no longer print and borrow its way out of its problems by issuing bonds as it once used to. High inflation leads to high interest rates and that means problems for people with debt and liabilities (like mortgages). When the Bank of England will cap out for interest rates we simply do not know. The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street is not entering into discussion about cutting interest rates yet and this does not bode well.

The UK’s cost of living crisis predates both COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war. As I stated in the last point, GDP has increased only marginally in the last 15 years and this small increase has been wiped out by the rising cost of goods and services, as represented by the CPI which has increased by 45.7% during this time. This has led to record levels of poverty not seen since the dark days of the 70s, such as a rise in homelessness and increasing dependency on food banks, problems that l will address in part two of this article.

Although inflation has come down the damage has been significant. The available data suggests that British households have accounted for the shortfall created by rising interest rates and high inflation by using their savings and by turning to credit cards.

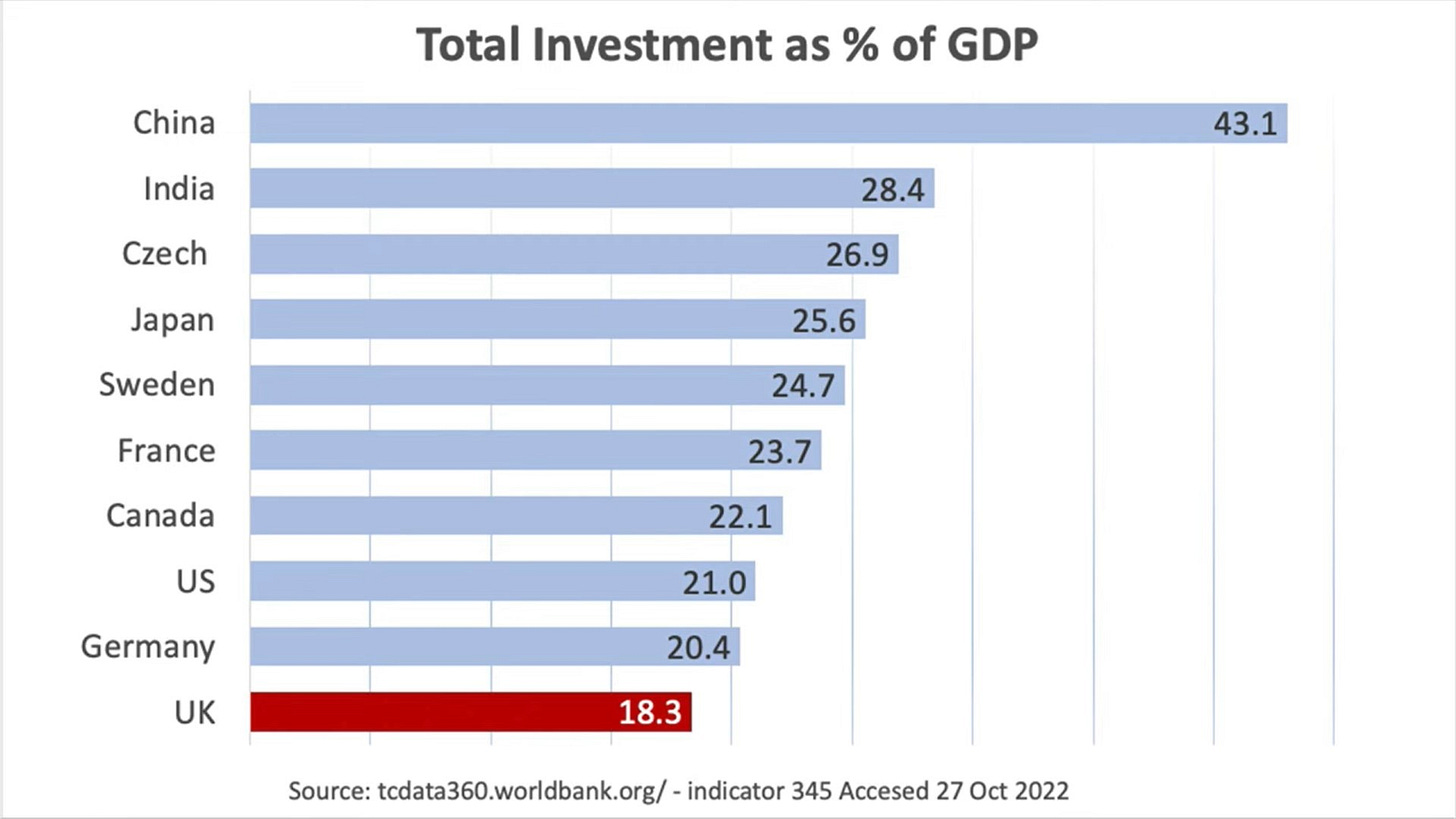

Low investment

The United Kingdom has a serious investment problem. Britain invests very little into research and development, capital machinery and equipment, training and new technology.4 This makes British businesses less competitive in the global market place. A lot of evidence suggests that trading in financial assets absorbs a lot of the capital that would otherwise be set aside for investment, this type of investment benefits a select few at the top of the economic pyramid but not the whole country.

The Guardian states that:

“Business investment is lower in the UK than in any other country in the G7, and 27th out of 30 OECD countries, ahead of only Poland, Luxembourg and Greece.”5

The same article points to half a trillion pounds in under-investment in the country.6

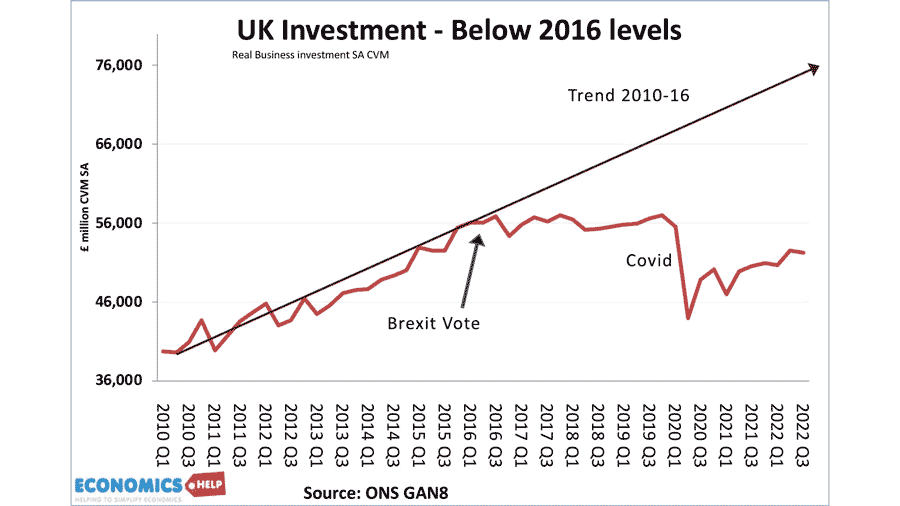

Low, porous investment is one of the biggest structural problems in the UK; it affects every part of the economy and the country is suffering because of years of underinvestment. The UK’s chronic investment problem has impacted wages, revenues and growth, trapping the country in what can only be termed as doom spiral; a self-reinforcing feedback loop of low investment leading to poor productivity resulting in low growth and declining living standards for all.7 Public sector investment was cut in the 2010s, during Britain’s now infamous period of austerity by the Conservatives. High interest rates disincentivise investment into industry as well.

The graph above demonstrates how private investment has really declined since Brexit.8 Indeed, it is not only Brexit that is to blame as many analysts have pointed to an extended period of ‘elevated uncertainty’ as the reason why the UK cannot attract more investment: the political turmoil that began around 2019, Brexit, fluctuating tax rates, the revolving door at Number 10 in particular Liz Truss’s brief reign as prime minister and the Conservative government flip-flopping on various policy issues have all played their part.

The kind of investment that the UK does pursue is highly questionable as well. Both the British government and UK business owners just seem to sell off assets entirely, instead of entering into a partnership with foreign investors wherein the UK retains a majority stake and the overseas investor has a minority stake. Britain has sold most of its public utilities to foreign consortiums as well as many famous companies to overseas buyers as well, much to the detriment of the nation. When the asset leaves so do the profits and revenue from the company. This will be explored more in part two of this article when I look at the effect of the privatisation of the country’s public utilities on the British economy and the mass sell-off of British companies too.

A chronic lack of investment over the years has led to declining infrastructure, an unskilled workforce and a poor utilisation of technology which leads to declining productivity resulting in low growth and lower wages for British workers. Ultimately, this cycle harms everyone as there is less money circulating in the real economy and it also means that the British government collects fewer taxes as well.

Skills gap

The skills gap problem is really an extension of the investment problem but it is worth highlighting separately. A report by the Learning and Work Institute in 2019 found that the UK skills shortage will cost the country £120 billion by 2030.9 Technology is the main area where the skills gap can be observed but the UK is not alone in this regard - this is a global phenomenon but seems to affect the UK more. Along with technology, vocational training is another big problem for the UK. Overall, employment is still below pre-pandemic levels with over 300,000 vacancies more than 2020.10 Early retirement, long-term sickness, an antiquated education system, a lack of investment and the reality of a post-Brexit Britain where the country struggles to compete for skilled workers from abroad are reasons cited for the skills gap. It is estimated that 20 percent of the workforce will be significantly under-skilled by 2030 and two-thirds of large UK businesses said they struggle to recruit employees with the skills they need.11

Low productivity

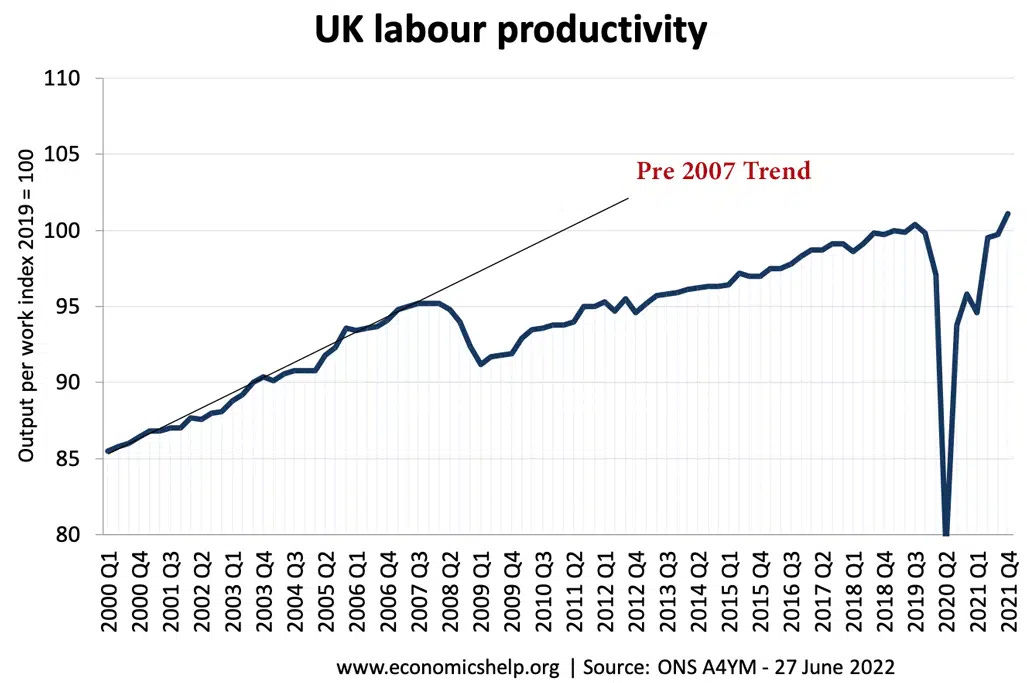

Yet another problem the UK has had for many years now is low productivity. Britain has some of the lowest productivity levels in the developed world meaning British people produce fewer goods and services per hour relative to other developed countries. Britain’s productivity lags behind the rest of the G7 average by about 17% and in the past 15 years productivity levels have averaged half a percent annually. The UK has had a productivity problem for a long time now, its origins remain unclear although the previously mentioned skills gap and lack of investment are likely two of the causes. Poor productivity causes inefficiencies across the economy, a workforce that is not productive will simply not generate the necessary levels of growth to keep the country competitive. Low productivity impacts wages as well; low productivity produces low revenues and this in turn leads to lower average wages, it is a vicious cycle. A decline in labour market participation is also a big reason why we have low productivity.

Real wage stagnation

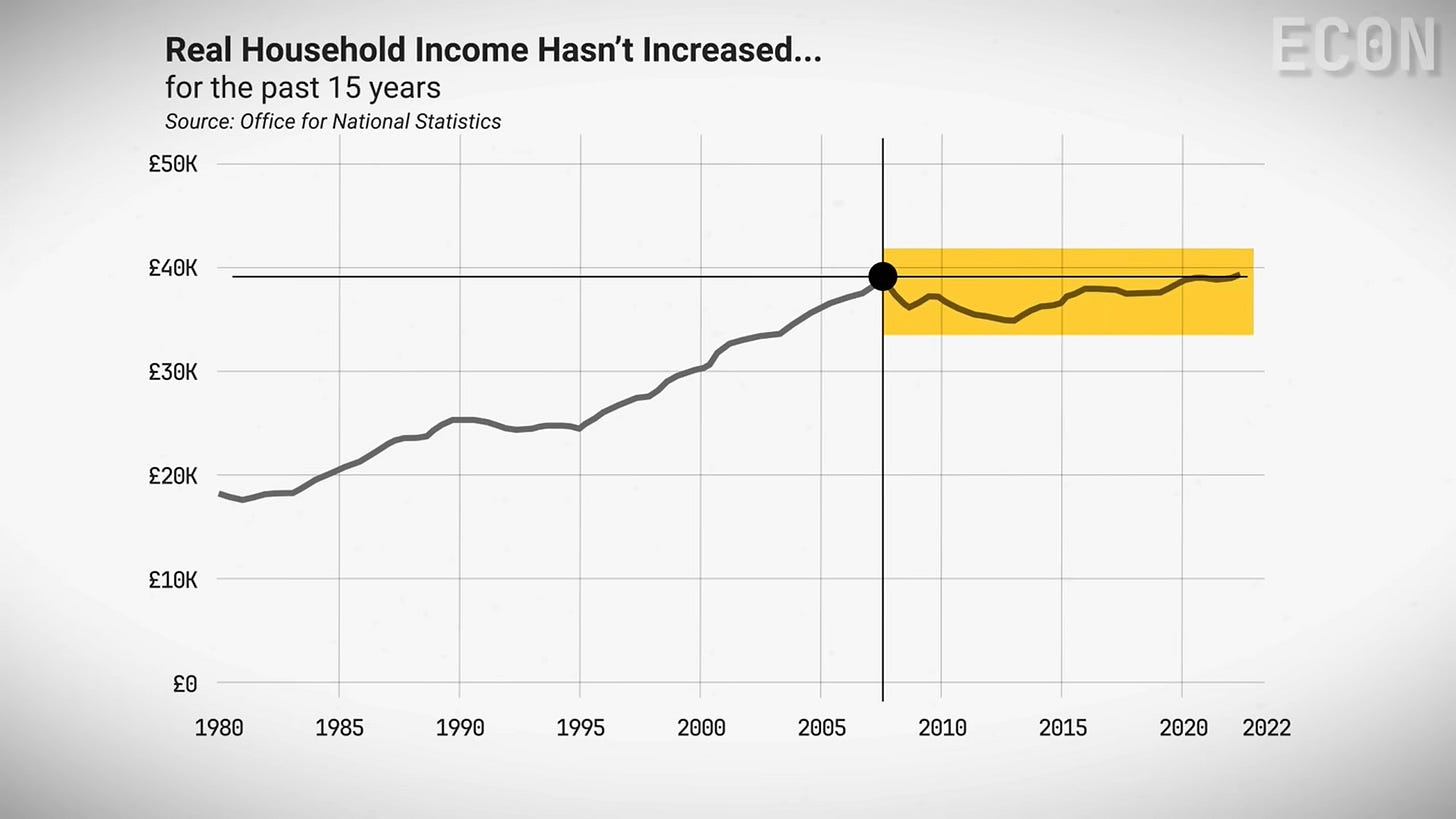

Real wages have not risen in 15 years. Alongside low-growth and economic stagnation, this has left workers across the country with £11,000 a year in lost wages.12

Going back even further, since 2008 the GDP per capita has risen by just £2,004 in 15 years, a rise of just 6.4%.

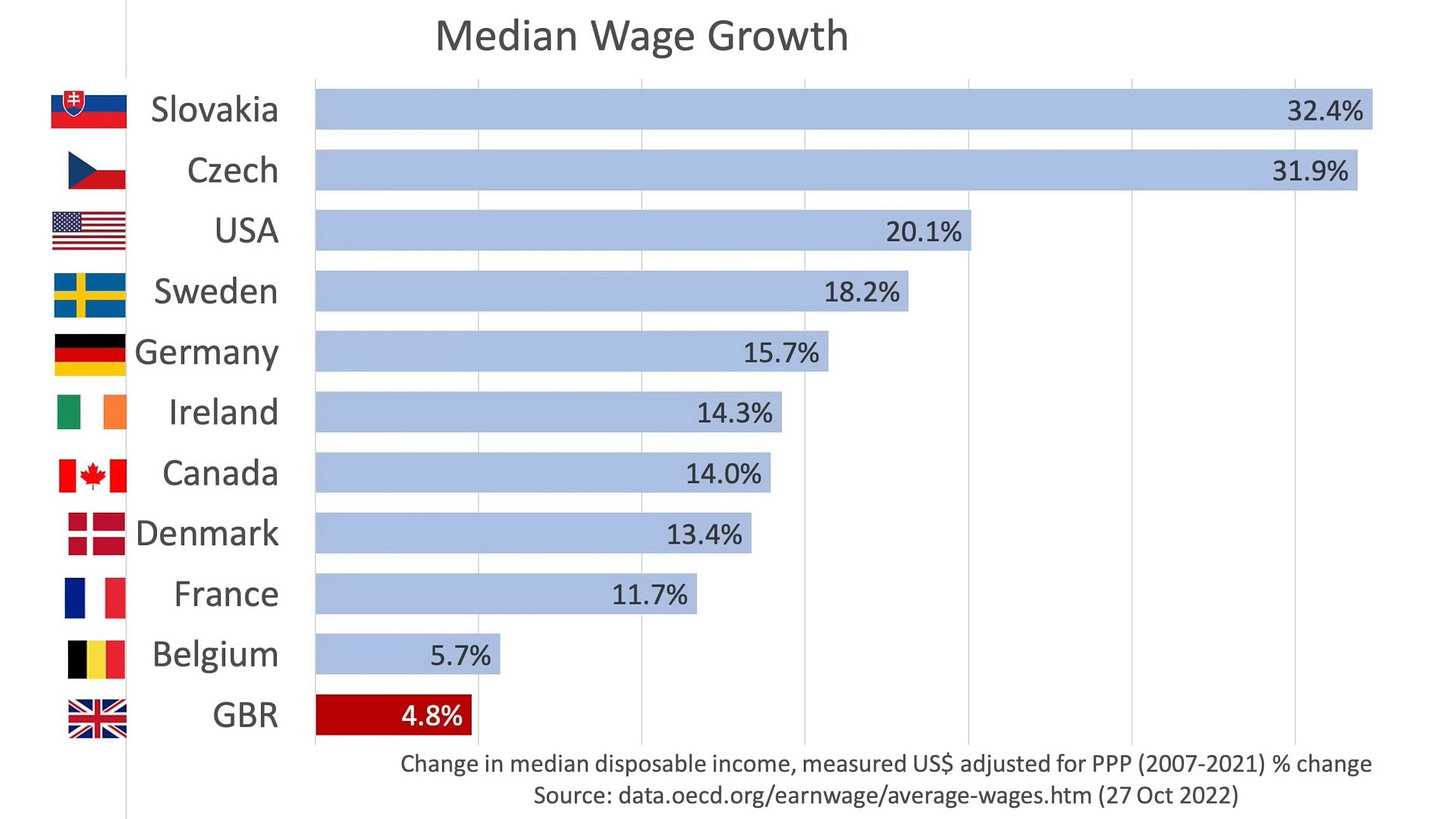

Real wages are down by 2.8% when compared with 2008, whilst they have risen on average by 8.8% in the OECD over the same period.13 This means less money circulating in the economy which ultimately harms us all, impacting wages and revenues. As the graph below illustrates, compared with other developing countries the UK’s median wage growth is very poor indeed.

Another explanation for the UK’s stagnant wages is the previously mentioned lack of productivity. The less productive a company or organisation is the lower the revenue it will generate and this will invariably result in lower wages.

Mass immigration has almost certainly impacted wages. In the last two decades the United Kingdom has witnessed unprecedented inflows of low-wage, low-skilled immigration into the country. Workers in the bottom quartile of wages have been particularly affected, a study done by University College London demonstrates that earnings in the lowest quartile of wages for companies that employ migrant workers resulted in wages declining by 4-5% compared with companies in the same sectors that do not hire migrant workers.14

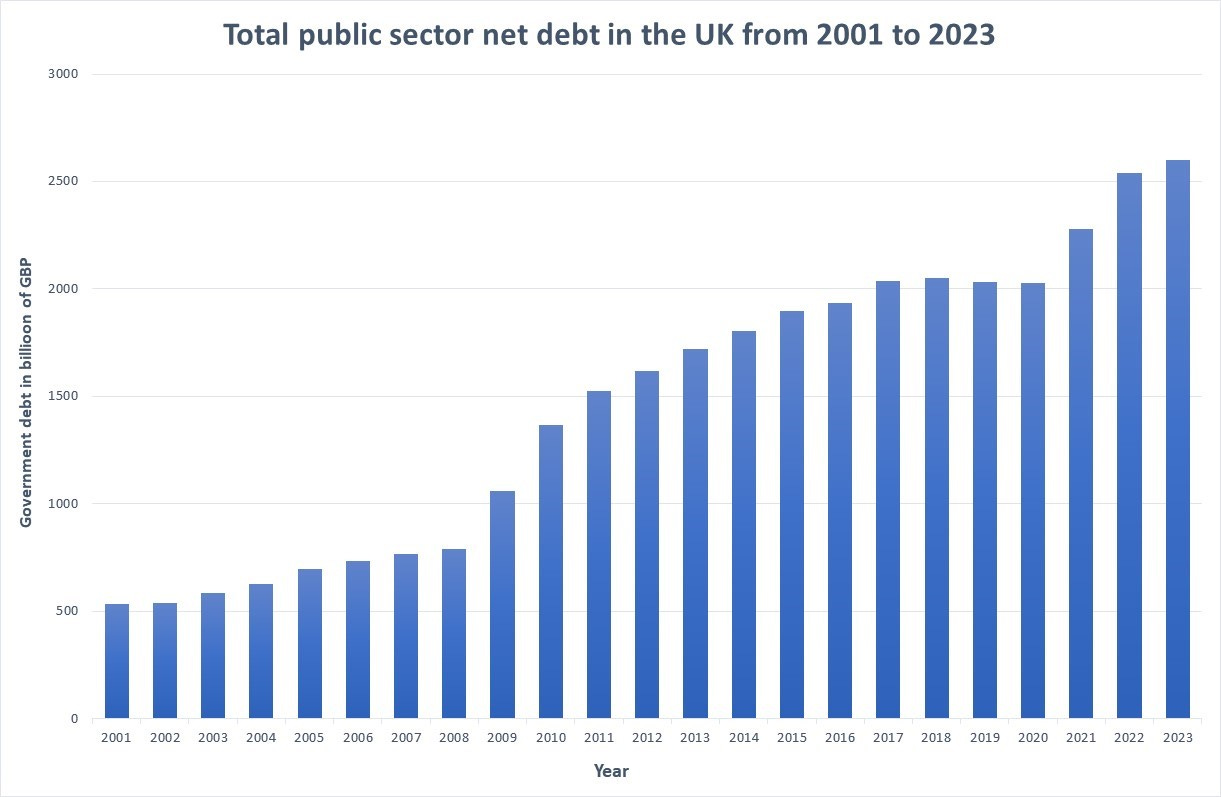

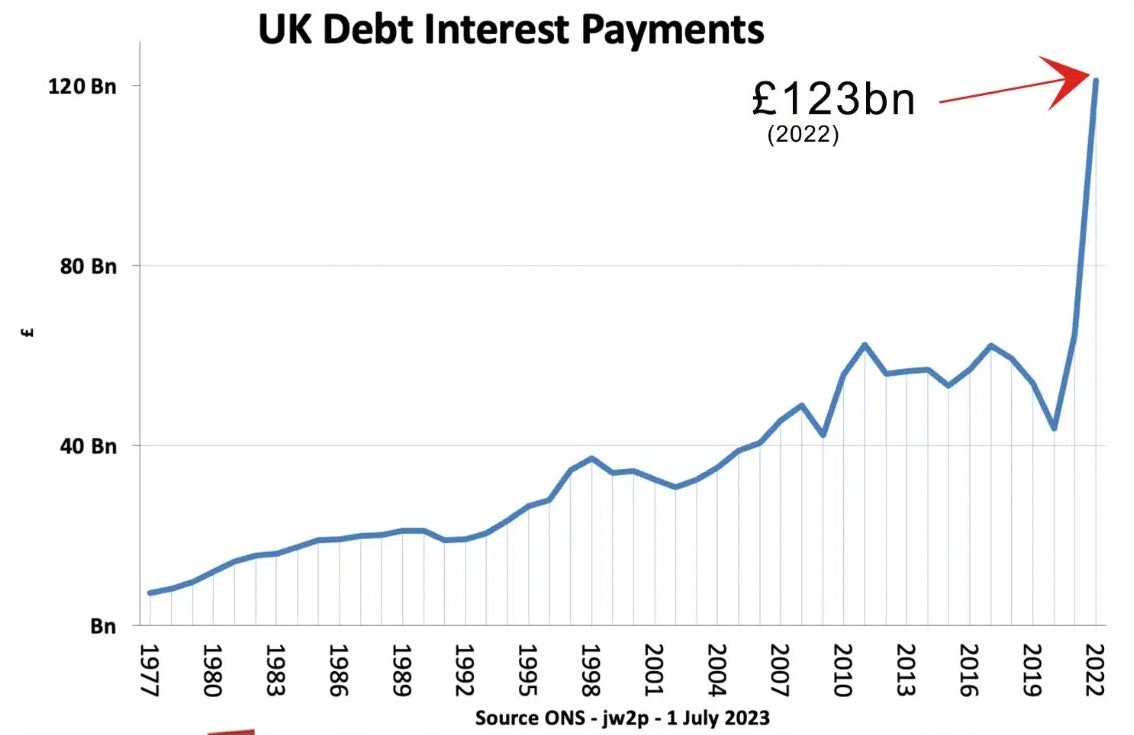

Debt

The national debt is the total amount of debt the British government owes, it currently stands at around £2.6 trillion with a debt-to-GDP ratio is 97.8%.15 Currently our debt is only slightly less than our total economic output, this is obviously very worrying.

In 2022, the UK spent £123 billion on debt interest payments - more than it spent on education.16 High interest repayments redirects spending away from things like healthcare, education, transport and emergency services.

Understanding the national debt is tricky, about a third is owned by the Bank of England but two thirds are held by outside investors. Currently, about a quarter of British debt is index-linked, meaning it is tied to inflation. The recent problem with sterling bonds leading to yet more inflation because of the recent round of quantitative easing where the Bank of England had to buy £65 billion on assets to prevent the pension fund collapsing.

In part two, I will look at property, mortgages, the privatisation of Britain’s utilities companies and Britain’s tax code. I will also look at how healthcare, education, infrastructure and other areas have all been impacted by UK’s struggling economy.

Thomas, B.D. (2023) 'UK economy ‘listless’ with little growth in four years,' BBC News, 13 July. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-66179998.

NIESR (2023) UK heading towards five years of lost economic growth - NIESR. https://www.niesr.ac.uk/publications/uk-heading-towards-five-years-lost-economic-growth?type=uk-economic-outlook.

BBC News (2023b) 'What is the UK inflation rate and how does it affect me?,' BBC News, 15 November. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-12196322.

TUC (2014) ‘Britain’s Investment Gap: Falling Behind’

https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Investment_Report_Final.pdf

Partington, R. (2023) 'UK economy in growth ‘doom loop’ after decades of underinvestment,' The Guardian, 20 June. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/jun/20/uk-economy-in-growth-doom-loop-after-decades-of-underinvestment.

ibid

The great British business investment problem The Financial Times (2023). https://www.ft.com/content/7fef1b85-a85f-4db8-95a3-f06b0ca43765.

Economics Observatory (2023) How has Brexit affected business investment in the UK? - Economics Observatory. https://www.economicsobservatory.com/how-has-brexit-affected-business-investment-in-the-uk.

Skills shortage (2022). https://www.theaccessgroup.com/en-gb/hr/resources/employee-talent-skills-development/skills-shortage/.

Tackling Britain’s dearth of skills and workers (2023). https://www.ft.com/content/e790c414-3640-4285-a3c3-ce0a222068ae.

Oxford Learning College (2023) Skills Gap Statistics UK 2023 | Oxford Learning College. https://www.oxfordcollege.ac/news/skills-gap-statistics-uk/#:~:text=An%20estimated%2020%25%20of%20the,required%20for%20their%20job%20role.

Rawlinson, K. (2023b) 'UK workers £11,000 worse off after years of wage stagnation – thinktank,' The Guardian, 20 March. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/mar/20/uuk-workers-wage-stagnation-resolution-foundation-thinktank.

Prane (2023) UK workers will miss out on £3,600 in pay this year as a result of wages not keeping pace with the OECD. https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/uk-workers-will-miss-out-ps3600-pay-year-result-wages-not-keeping-pace-oecd#:~:text=The%20analysis%20shows%20how%20the,average%2C%20over%20the%20same%20period.

Bryson, A. (2019). Migrants and Low-Paid Employment in British Workplaces. At https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10066465/3/Bryson%20wes%20migrants%20revised%20paper%20v4.pdf

Islam, B.V.S.-P.& F. (2023) 'Cost of national debt hits 20-year high,' BBC News, October. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-67002195.

ibid

You lament the sale of British companies to foreign investors, but I seem to recall reading that conversely UK investors own considerable numbers of foreign companies. If that is so then it works both ways.

It is hard to find much information on this with web searches, since most return "the UK is being sold abroad" type articles. But the following looks like an interesting relevant discussion. (The person posting the initial question also complained of exactly the same difficulty I had in finding relevant information!)

https://www.reddit.com/r/unitedkingdom/comments/5dbjh2/what_do_british_companies_own_abroad/

I think another motive for the UK Government in allowing company and utility sales to foreign investors, besides the obvious short-term benefits of the UK gaining the sale proceeds, may be to try and insulate the companies somehow from industrial action by bolshie UK trade unions. But how well that works, if at all, is hard to tell.

"I don't understand. I thought that the hundreds of thousands of net migrants every year would turbo-charge the UK economy!"

In all seriousness, a lot of British economic history since 1965 seems to be the boomers looting this country and kicking away the ladder - QE/money printing, high income taxes to pay for state pensions, high house prices, immigration leading to low wages, and saddling their kids with student debt to have something to boast about whilst they had tuition paid for them.